Introduction

This is the Day 4 Journal on my Linux Upskill Challenge , yes, this is the lesson when you get in deep with the Linux File System, I also learned about how to install packages in Ubuntu Linux with APT.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Installing packages in Ubuntu Linux

- Linux File System

- Questions I asked myself 🤔

- Related Notes

Installing packages in Ubuntu Linux

- Think of packages like programs or applications (apps) that you install on your phone.

- Like the “App Store” or the “Market” on your phone, in Linux we call them Package Managers.

- One of the most popular (if not the most used) package managers in Ubuntu (and other Linux distributions based on Debian) is apt.

- APT stands for “Advanced Package Tool” and is used to install, update, and manage software packages.

- For example, to install a package, you can use the command:

sudo apt install <package-name> - To update the list of available packages and their versions, run:

sudo apt update - And to upgrade all installed packages to their latest versions:

sudo apt upgrade

- If you know a keyword or part of the description of a package, you can search for it using the

apt searchcommand. For example:

apt search "midnight commander"- This will display a list of packages matching the search term along with a brief description of each:

mc/noble-updates,now 3:4.8.30-1ubuntu0.1 arm64 [installed]

Midnight Commander - a powerful file manager- Here we can see

mcis the package name for the Midnight Commander package (application). - To install the package with apt you need to use

sudo, unless you’re already logged in asroot.

sudo apt install mc- Package managers like apt make it easy to handle dependencies and ensure your system stays up-to-date.

- There are other package managers available for Debian-based Linux distributions.

- For Red Hat-based Linux distributions, the equivalent of

aptisyum. (but that’s a completely different story! 🙂)

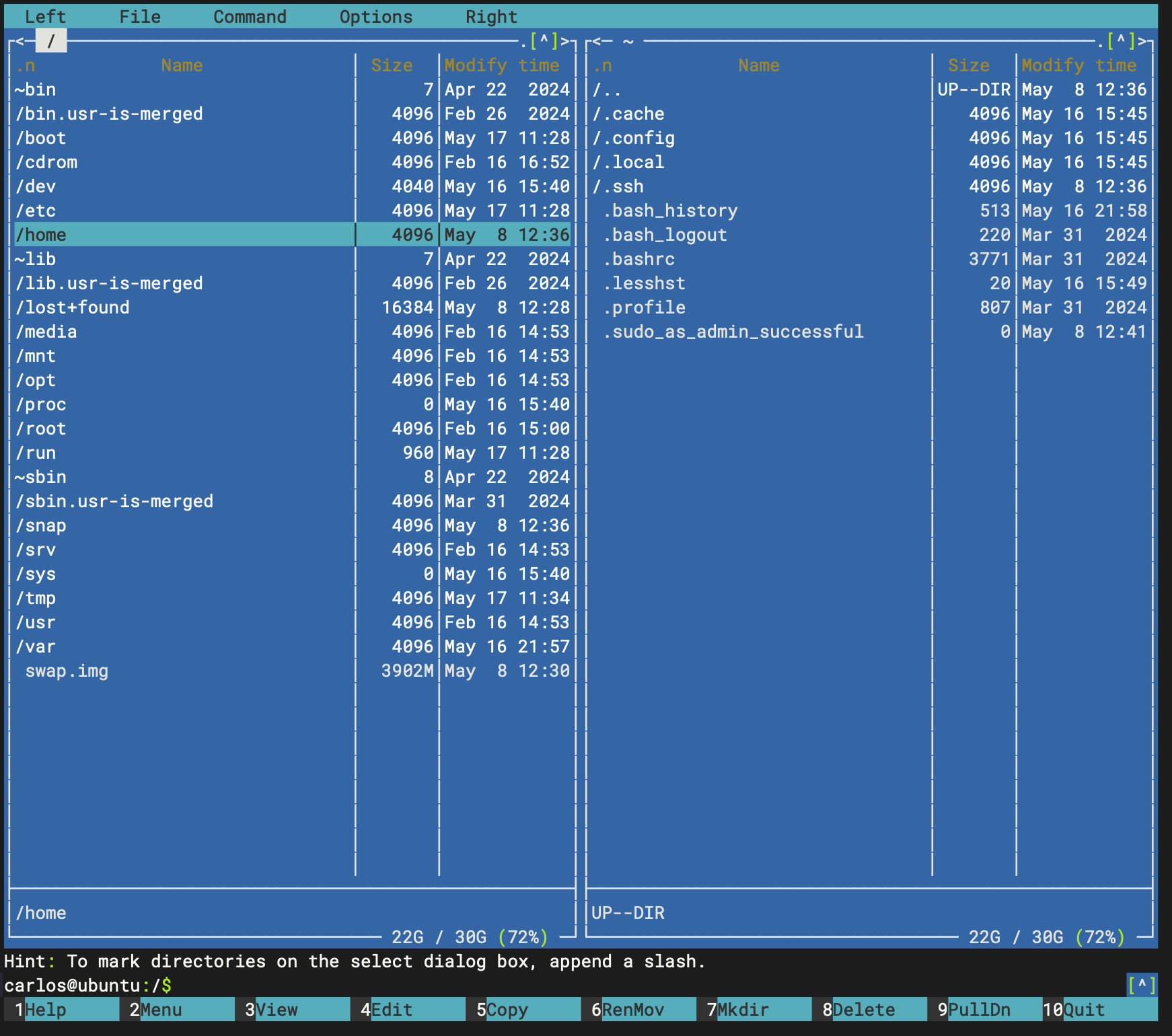

Now that we’ve installed Midnight Commander, we can use its retro interface to easily navigate the Linux file system.

The Linux File System

- The Linux operating system has a standard file system structure. At first, it might seem a bit intimidating—especially if you’re only familiar with Windows, where you have the C: drive, D: drive, and various folders within each. With Linux, it’s a totally different beast.

- The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) defines the structure of file systems on Linux and other UNIX-like operating systems. However, Linux file systems also contain some directories that aren’t yet defined by the standard.

- If you want to read the official manual of the file system hierarchy, type

man hier

/ ⇒ (La Raiz 🫚) The Root Directory

- Everything on your Linux system is located under the

/directory, also called the root directory. (Don’t confuse it with the/rootdirectory.) - In Linux you don’t have drive letters like C: or D:. Everything is under

/, even if you have different physical drives and partitions— all of them will be under/.

/boot ⇒ 🥾 Boot files

- Contains all the files needed to boot the system, including the currently installed Linux kernels and their supporting files.

- The GRUB bootloader’s files are stored here as well.

- It is better not to mess with this directory!

/etc ⇒ ⚙️ Configuration Files

- Key configuration files are stored here, and in subdirectories inside.

- Most of the files here are simple text files.

- Some interesting files under

/etc:/etc/passwd: contains basic information about each user account (like username, UID, default shell, etc.). Passwords are stored in another file./etc/ssh/sshd_config: this is the configuration file for the SSH daemon (sshd), which acts as the server for the SSH connection. (The client is on your computer! 💻)

/home ⇒ 🏠 User Home Folders

- Each user in the system will have a folder inside

/home(for example/home/carlos,/home/ubuntu). - Inside each folder we have user data files, user-specific configuration files, and folders. Many of them are hidden (use

ls -lato list them). - Each user can only write in their own home folder.

- Example files and folders found in a home folder:

.bashrc,.profile,.ssh/,.config

/root ⇒ ⛪ The root home directory

- Instead of being inside

/home, the root user has their own home directory in/root.

/bin ⇒ Essential binaries 🧱

- The

/bindirectory contains all the essential system binaries that Linux needs to function — even when it boots into a special recovery state called single-user mode (you can think of it like Safe Mode in Windows). - It contains important core command-line tools that must be available even if no other filesystems are mounted yet — such as

ls,cp,mv, and thebashshell. - It traditionally has two sibling directories:

/sbin(for essential system binaries for administrators) and/usr/bin(for general user binaries that are not critical for boot).

/sbin ⇒ System administration binaries 💾

- The

/sbindirectory contains essential system administration binaries used for system booting, repairing, or managing services — likefsck,reboot, andifconfig. - These tools are generally intended for the root user or administrators, and may not be in a regular user’s

$PATH.

/usr ⇒ 🧰 user-space programs and tools

- It contains applications and files used by users, as opposed to the system itself.

- These files and folders are meant to be read-only for regular users, unless you’re installing something manually into

/usr/local. - These files are installed and managed by the package manager (apt, dnf, yum, etc.).

- In some distros (especially immutable or container-focused ones like Fedora Silverblue, Alpine, or embedded systems),

/usris even mounted read-only at the filesystem level to improve security and stability. /usr/bin,/usr/lib,/usr/share, and/usr/localare examples of directories inside/usr.

/usr/bin ⇒ 🛠️ main executables for users and apps

- The

/usr/bindirectory contains most user-level commands and applications that are not essential for booting or single-user mode. - It’s often much larger than

/binand includes tools likegit,nano,python,gcc, etc.

NOTE

⚠️ Modern Linux systems often merge

/binand/usr/binusing symbolic links. So the physical separation may no longer exist — but conceptually, this is still true.

/usr/lib ⇒ 📚 shared libraries for installed programs

- Contains the libraries for the non-essential user-level binaries located in

/usr/bin.

/usr/local ⇒ 🧪 custom software installed manually

- Locally compiled programs not managed by the package manager.

/var ⇒ 📝 logs and variables

/varstands for “variable” — it contains files that change frequently, like logs and temporary data.- It is the writable counterpart to the

/usrdirectory, which must be read-only in normal operation. - It stores system logs, like authentication attempts and errors, usually inside

/var/log. - It also holds spools and queues — like for print jobs, mail, or cron jobs.

- If a system is acting weird or you’re running out of disk space,

/varis often the first place to check.

/var/log ⇒ 📂 system and service logs

- This is the folder where Linux keeps log files from the system and various services.

- Most of the files here are simple text files.

- Some interesting files under

/var/logare:/var/log/auth.log: Captures all authentication events — like login attempts, sudo usage, and SSH access./var/log/syslog: General system activity log, useful for debugging services and applications./var/log/kern.log: Messages from the Linux kernel, helpful when troubleshooting hardware or low-level issues./var/log/dpkg.log: Logs of all package installations and updates (on Debian/Ubuntu systems)./var/log/boot.log: Records messages during the system boot process, helpful for startup issues.

/tmp ⇒ 🧊 temporary files for programs

/tmpis used to store temporary files created by programs, scripts, or the system itself.- The data here is not meant to be permanent — it’s usually deleted on reboot or after a certain time.

- Applications use it for things like installers, locks, or temp caches while they run.

- You can manually delete files here to free up space, but be careful not to remove in-use files.

/dev ⇒ 🔌 devices as files

/devcontains device files that represent your hardware (like disks, USBs, and terminals).- Linux treats devices like files, so you can interact with them via commands (e.g.,

/dev/sda,/dev/null). - It includes both physical devices and virtual ones (like

/dev/random,/dev/tty). - Device files are managed by the udev system and updated automatically as devices are added or removed.

/proc ⇒ 🧠 system and process info

/procis a virtual filesystem that shows real-time information about running processes and the kernel. Similarly to/dev, it doesn’t contain regular files but virtual representations of system internals.- Each process has a folder like

/proc/1234containing its memory, open files, and status. - It includes files like

/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/meminfo, and/proc/uptime— great for monitoring. - These files aren’t stored on disk — they’re generated live by the kernel when you access them.

/sys ⇒ 🛠️ kernel interface to hardware

/sysis another virtual filesystem, used to expose and control kernel data structures.- It provides detailed info about hardware devices, drivers, and kernel modules.

- It’s commonly used by tools like

udevadm,systemd, orudevto detect and manage hardware. - You can even tweak some kernel parameters from here (with caution), usually under

/sys/classor/sys/block.

/lib ⇒ 📚 Essential common libraries

- This folder contains libraries needed by the binaries found in

/binand/sbin. - Linux libraries are shared collections of precompiled code that programs can use to perform common tasks.

/media & /mnt ⇒ 💽 mount points for external and manual storage

- Both

/mediaand/mntare used as mount points — places where external or additional filesystems are attached to the main system. /mediais typically used by the desktop environment or automount system to mount USB drives, SD cards, and external disks automatically (e.g./media/carlos/USB)./mntis usually reserved for manual or temporary mounts done by system administrators (e.g. mounting a backup disk or ISO).- You can mount a filesystem to either, but by convention: automated →

/media, manual →/mnt.

Questions I asked myself 🤔

- What a Shell is?

- What Happens When You Connect to a Server via SSH and Run a Command?

- What is a Daemon in Linux?

- What is a Binary in Linux?

Related Notes

Nota diaria: 2025-05-08